Will International Workers Address our Skills Shortages

Article by Andrew Trinh

“We’ve Golden Soil and Wealth for Toil”, but will International Workers Address our Skills Shortages?

Australia is (almost) ready to reopen its borders. It’s a timely decision as various industries have announced their appetite for growth as they move from recovery to expansion.

Infrastructure Australia reports a workforce supply gap of almost 93,000 jobs by 2024 based off known and committed public infrastructure works. Curiously, The Tech Council of Australia aims to deliver one million tech jobs by 2025. It, too, is projecting a shortage of 93,000 tech jobs.

December 1st would have seen the return of fully vaccinated international students and eligible visa holders, but the decision has been delayed by at least a fortnight due to the new Omicron variant.

Having heavily relied on migration solutions for economic growth in the past, will international workers come to Australia’s rescue in the post covid era?

According to INSEAD’s 2021 report, Australia ranks as the 11th most competitive talent magnet: highly capable of attracting, growing, and keeping global talent.

However, there will be countries in similar positions trying to hold onto their own skilled workers.

It’s a competitive field, with traditional adversaries in the United States, United Kingdom, and non-traditional newcomers Japan, Canada, and Kazakhstan identified in the global war for talent.

However, the Federal Parliament’s Migration Committee concluded Australia must do more to remain competitive, offering more attractive residency pathways and work rights, particularly for students.

While skilled workers and students are highly sought after, Australia has an untapped workforce, including refugees from Iraq, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Myanmar.

Betina Szkudlarek from the University of Sydney Business School says refugees shouldn’t be seen as “a generic pool of low-skilled employees…They are extremely diverse [and] every employer could find a very driven, committed employee within that talent pool.”

While high-level discussions around visa and permanent residency pathways are part of the solution, it is a businesses’ responsibility to attract and retain their talent.

The talent landscape has been transformed

Lockdowns have reconstituted workplace practices, and new standards about where and when employees can work have been set. Successful experiments in remote productivity have resulted in a renewed demand for work-life balance and consideration for work satisfaction.

Today’s market is an employee’s market. Employees are not only considering how they work but why.

Countless post-covid studies from Gallup, McKinsey and Company, and others say the same thing: it is about the employee experience.

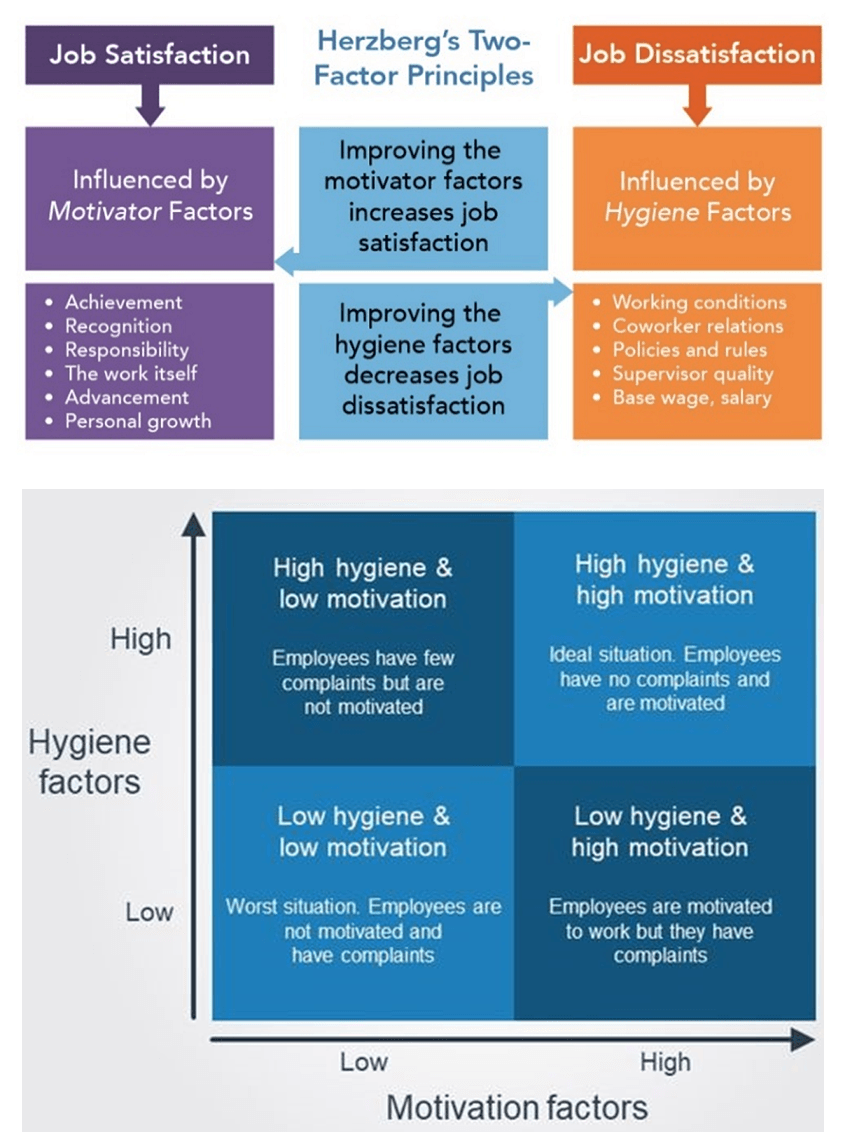

However, this isn’t new. Consider Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory from the 1960s. These are the factors that cause job satisfaction and dissatisfaction.

Critical to understanding this theory is that improving one side of the equation does not necessarily improve the other.

For example, increasing a worker’s salary for the same position is not a replacement for additional responsibilities or personal and professional growth. In addition, seeking employees’ feedback and plotting them on the matrices will help determine the factors which need attention.

Managers and employers must improve all factors to attract and retain their staff. These strategies will be critical to every business if they are to address their skills gaps.

INSEAD advises that: in the post-covid era, “organisations that focus on outcomes and flexibility will attract the best and the brightest”.

In the coming months, thriving organisations will be those aiming to be employers of choice.